When an Orange County Supreme Court judge voided Newburgh’s good-cause eviction law last year, she said there was a “direct conflict” between the local measure — which limited rent increases and constrained a landlord’s powers of eviction — and state law, where such protections do not exist. This was the same legal reasoning that brought down good cause in Albany last summer (which an appellate court upheld this March) and in Poughkeepsie earlier this month. A lawyer representing one of the landlords in the Newburgh case put the court’s view plainly: “Newburgh just doesn’t have the power to draw a circle around Newburgh and say, ‘Those state laws won’t apply here.’ It’s really that simple.”

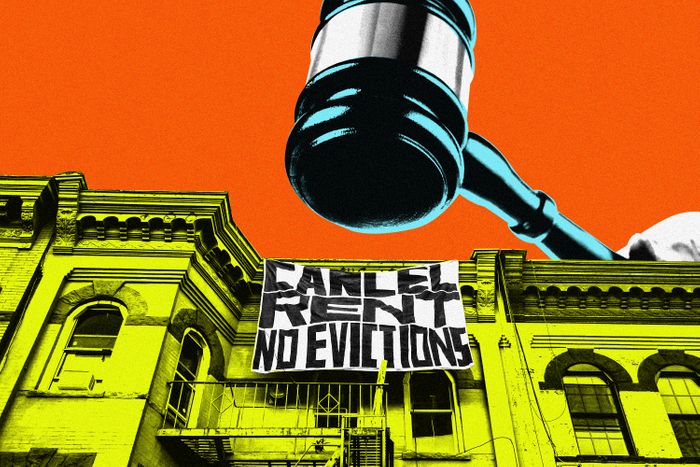

Tenants and local officials had hoped the piecemeal approach would hold as the state-level good-cause bill stalled in the legislature for the better part of four years. The good-cause law would create rent-hike caps for market-rate tenants and prevent landlords from ending a tenancy unless they had cause, such as failure to pay rent. In effect, it’s extending protections similar to rent stabilization to millions of market-rate tenants across the state. With good reason: A recent report by Cornell University found that in 2022, eight out of ten counties with the highest rates of eviction filings were upstate. A Legal Aid brief in support of good cause found that in Albany, the average fair-market rent for a two-bedroom rose from $1,084 in 2019 to $1,788 in 2022. The median rent for a one-bedroom in Ulster County shot up 27 percent between 2016 and 2020. Extreme housing shortages upstate were being fueled in part by an influx of wealthier New York City expats. If the state would not protect tenants, the hope was that at least localities could.

Then came the lawsuits. In Newburgh, where the median household income is $47,900 and tenants make up 70 percent of the population, Michael Acevedo was among a small group of landlords to challenge the city’s good-cause law. (Acevedo, the president of the Orange County Landlords Association, once worked as the city marshal in charge of evictions, telling the local paper in 2005 that Newburgh needed to weed out the poor: “Who cares where they go?”) Deborah Pusatere, one of the landlords involved in the challenge to Albany’s good cause, had said of her tenants’ nonpayment during COVID eviction moratoriums that “bad behavior is contagious” and “it spreads like cancer.” In Kingston, where realtors have started telling tenants with sticker shock that the city is “the new Brooklyn,” Rich Lanzarone, the landlord director of the Hudson Valley Property Owners Association, told the Guardian that the realities of the new market shouldn’t be a problem “if you’re a relatively young and mobile person.” Kingston was the first city upstate to opt into rent stabilization and enact a 15 percent rent reduction. (After Lanzarone’s group sued, the courts upheld stabilization, but struck down the reduction; both sides are appealing.)

Michael Townsend, a retired veteran living in Albany whose tenant association is fighting for good cause, said that his landlords had tried to raise the rent on his one-bedroom last year from $670 to $1,150 — nearly his entire fixed income. He refused to pay but then the law was struck down. “We felt like that was a straight slap in the face,” Townsend said. Now his landlords are planning to raise his rent in May by nearly 20 percent — to $800. “I am living off of what I’ve saved up,” he said, “but if I don’t find some work soon, I’m gonna be in trouble.”

Even with the court losses, tenants and organizers are confident good cause can prevail and are redoubling their efforts to get it through the state legislature. Andrew Scherer, professor and director of the Housing Rights Clinic at the New York Law School, said that if good cause passes on the state level, he expects a landlord challenge, but the substance of the bill is similar to laws already on the books. “It’s not really different from what’s been in effect continuously since World War II in New York City,” Scherer said, referring to laws regulating rent-stabilized units, which require landlords to have cause when terminating a lease.

It’s an uphill battle. The state bill has been idling since 2019, and Kathy Hochul has continuously deflected when asked to back it. (It was notably left out of her housing plan.) As the state budget deadlines approach this week, advocates are making a renewed push for good cause. “All of the sudden, constituents are going without protections they’ve enjoyed for the last couple years,” Aaron Narraph Fernando, a spokesperson for the Hudson Valley–based organizing group For the Many, said. “If judges are so far unanimously saying that cities can’t protect tenants, then the state has to act.” At a recent rally where 36 pro–good cause activists were arrested after occupying Hochul’s office, tenants chanted “Shame” as James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York, walked through the building. Whelan kept his AirPods in.